時間。鉛筆を下ろします。国として、私たちはテストに汗を流し、成績の悪い学校を分析し、基準とカリキュラムを破壊し、すすぎと繰り返しを繰り返してきました。私たちは教室の机の椅子を問題に投げつけましたが、数学と科学のリテラシーに関しては、Cマイナスよりも稼いでいません.完璧なテストはありませんが、2012 年の留学生評価プログラムによると、15 歳のアメリカ人は、経済協力開発機構の 34 の加盟国のうち、数学で 27 位、科学で 20 位にランクされています。 (12 月 6 日更新: 本日発表された 2015 年の評価では、米国は 35 の OECD 加盟国中、科学で 19 位、数学で 31 位にランクされました。)

パズルは状態の重ね合わせで持続します。基準が低すぎるか、それとも挑発的に高すぎるか?学校に適切かつ公平に資金を供給するにはどうすればよいでしょうか。正しいことを正しい順序で教えているか?それとも、調査のプロセスに関するものですか?標準化されたテストは、テスト業界以外の誰にも役立ちますか?従来の教室は学習に役立ちますか?テクノロジーを追加するか、削除する必要がありますか?

これらの問題には注意が必要です。しかし、テストの点数や新しい基準をめぐる公的な議論の中で失われがちな変数の 1 つは、間違いなく最も重要なものです。それは、間違いやすい人間が、学習への欲求と感謝を与える役割を担っているということです。このアメリカのビザンチン教育システムの要にスポットライトを当てるために、Quanta Magazine 4 人のマスター科学と数学の教師の後を追って教室に向かいました。ここに彼らの物語があります。

試す

5 月 23 日月曜日の早朝、アップタウン 5 号線の電車が地下のシャフトから空に向かって急降下し、ブロンクスの光に昇ります。車は大通り、ボデガ、一戸建て住宅の上にある高架の線路の上をうめき声を上げ、木のてっぺんや錆びた低層の非常階段のエッシャー風の迷路に沿って進みます。 12 駅後、行列の最後尾に差し掛かったところで、残りの数人のライダーがベイチェスター アベニューに出て行きます。丘の上には、ベイチェスター中学校の本拠地である三角波のマーキーを備えた、ずんぐりした市松模様の建物があります。

ベルが鳴ります。 「コーネル大学」のホームルームの 2 階にあるこのホームルームは、子供たちが早くから頻繁に大学について考えられるようにするために名付けられたもので、チャンナ カマーは大きな声とさらに大きなチェシャ猫の笑顔で生徒たちに話しかけます。 、 9 、 8 … 」 生徒たちはノートを前にして机に着くまで、バックパックをかき回しながらスクランブルをかけます。彼らは皆、背中に大きな白い文字が書かれた青い学校発行のシャツを着ています。年間を通じて、TRUST、TRAIN、THANK の文字が入ったシャツを獲得しています。今日のシャツには TRY と書かれています。

それらの周りには、「人生は複雑です。それに対処しましょう」、「陽子のように考えて、前向きになりましょう」というアドバイスのポスターなど、試してみることを思い出させるものがあります。教室の前には、その日のスケジュールが書かれたホワイトボードの上に、「パラメーター」、「構文」、「データ型」などの語彙とその定義が印刷されています。部屋の奥にある棚には、松ぼっくりや貝殻を詰めた透明な容器が置かれています。以下は、堆肥、土、植物、岩、ヒトデ、安全ゴーグルの容器です。

高さ 2 インチのプラットフォーム サンダルを履いて 5 フィート 1 で立っているカマーは、特大の存在感を放っています。彼女の声は部屋を簡単に満たしてくれますが、大きな笑い声を上げたり、良い行動でスコアカードで 100 点を獲得した生徒 (今日はショーネイ) をほめたたえたりする場合を除いて、声を上げることはめったにありません。カマーは、何年にもわたる格闘技とマラソンのトレーニングから生まれたアスレチックな体格を持っています。アマチュアの競争力のあるボディービル、現在は包帯を巻いた 40 歳の膝に打撃を与えた活動は言うまでもありません。生まれつき好奇心旺盛でキャリア チェンジャーである Comer は、看護学生として高度な生物学コースを受講し、グループ ホームの建設を調整する仕事のために物理学と工学を学び、教師になった後、いくつかの夏休みを科学分野の調査に費やしました。

「科学と関係のないものは何もありません」とカマーは授業の後に言いました。 「生徒たちが自分の周りの世界がどのように機能するかを知ることは、私にとって非常に重要です。」

しかし、科学を学ぶことは別の言語を学ぶようなものであり、ベイチェスターの生徒のうち学年以上のレベルで英語を読める生徒は 10% しかいない、と彼女は言いました。問題を複雑にしているのは、小学校の教師が科学を教えることに対する関心や能力が大きく異なることです。子供たちがカマーの 6 年生のクラスに到着するまでに、何人かは事実上科学をまったく知らず、何人かは教科書しか読んでおらず、他の子供たちは完全な実験を行っていました。中学生レベルでも、「テストがあるので科学は優先事項ではありません。数学と [国語] の高い賭け金は、子供たちの進級に基づいており、教師の評価に基づいています。」

さらに事態を複雑にしているのは、この学校が 42 棟の建物と 2,000 戸のアパートを擁し、ギャングによる暴力の歴史がある区最大の公営団地の向かいにあることです。

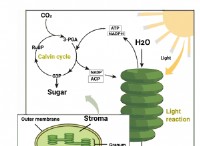

Comer は、ビデオ、歌を含むありとあらゆるものを使用します (彼女は生徒に拍手とチャントをさせます:「S-C-I-E-N-C-E、科学者は私たちがするものです! 解決します。作成します。調査します。評価します。通知します。分類します。実験します!」)、運動感覚学習 (オン今朝、彼女は学生に呼びかけて、分子がどのように振る舞うかを演じさせます)、物理モデル (学生は Play-Doh の小さなボールを転がして分子の特性をモデル化します)、そして分析的な読み物をして、「すべての子供が自分のレベルに基づいて何らかのアクセス ポイントを得られるようにします。 」授業中、彼女は再帰的な切迫感を持って生徒に質問します。私は知る必要があります」とキッカーが続き、「どのように知っていますか?」次に、意味を強化し、驚きを呼び起こす実践的な実験を行います。

しかし、彼女が 2007 年に教師としてのキャリアを始めたとき、ブロンクスにあるアーバン アセンブリー アカデミー オブ ヒストリー アンド シチズンシップ アカデミーと呼ばれる小さな高校で、その後閉鎖されました。 「私は輪を飛び越えたり、頭の上に立ったりして、子供たちに興味を持たせようとしていました」と彼女は言いました. 「毎日家に帰ると、ただ戦ったような気分でした。」彼女は、「誰もが自分の体について知りたい」と考えて、人体のユニットを始めたことを覚えています。学生が「ああ、お嬢さん、うまくいく限り、それがどのように機能するかはどうでもいい」と言ったとき、彼女は盲目的でした。彼女は、子供たちを科学に夢中にさせることができる低学年に落とす必要があることを知っていました.

6 年生レベルでは、Comer 氏は次のように述べています。彼らが本当にある程度のエンゲージメントを持っていれば、すべての基本を学ぶことができると思います。」

高校レベルで 4 年間過ごした後、Comer は Baychester の創立 6 年生の理科教師になりました。学校の創立校長であるショーン・マンガーは、カマーが雇われた直後に、彼女が何年にもわたって購入した科学教材を積んだU-Haulに現れ、「あなたは本気ですか?」警備員より。そして昨年、彼女はすべての子供たちが歌っていた人気のラップソングを取り上げました — Fetty Wap の「Trap Queen」は、ガールフレンドにクラックコカインの作り方を教えている男についてのものです — BGM を見つけ、学生が書き直すコンテストを開催しました。科学的な内容の歌詞。優勝した学生は、コロンビア大学で開催された Science Genius コンテストで、水循環に関するリメイクを行いました。カマーはまた、大学の SECME コンソーシアムからの資金提供を受けて放課後のエンジニアリング クラブを開始し、その後、NASA から 2,500 ドルのサマー オブ イノベーション助成金を受け取り、そのための物資を購入しました。 「そのようなことを彼女が起こすのです」とマンガルは言いました。

カマーはまた、学生が自分たちの問題を解決するよう強く主張することでも知られています。副校長のエリザベス・リーベンス氏は、学生は「科学の歴史を学ぶ機会を得るのではなく、科学の歴史を学ぶ機会があまりにも多い」と述べています。それでもリーベンス氏は、科学クラブの学生グループがカマー氏にアイスクリーム作りの実験を手伝ってほしいと頼んだ後、カマー氏が「戻ってプロセスを確認してください」と言ったとき、驚きました。彼らはトイレに行き、最新のバッチを捨てて最初からやり直しました。

「私はそれを生産的闘争と呼んでいます」とカマーは言いました。 「ここで成長が起こります。」

ミーティングでリーベンス氏は、カマー氏は「子供たちのために認知作業を行うのをやめるよう私に挑戦しました。彼らはそれを行うことができます。カマーにとっては、それは「人生の教訓であり、大人が何ができるかを決める前に、子供たちに何ができるかを見てもらうことへの大きな期待でもあります」と彼女は付け加えました。

ベイチェスターの学生にできないことを伝えているすべてのメッセージがありますが、カマーは彼らをあきらめません。 「これらは私の子供です」と彼女は言いました。 「これは私のコミュニティです。」

闘争

5 月 25 日水曜日、イースト サイド コミュニティ高校で、ソニ ミダは 10 年生の幾何学クラスをマンハッタンの路上でのレッスンに連れ出しました。生徒たちはたくさんの障害に直面します:ゴミの山、ドッグラン、サイクリスト、建設、熱波、タクシー、そして彼の注意の対象から簡潔な叱責を受けるキャットコールゴーカー. 「どうして私を見るの?」 17 歳の Nasifa さんは言います。「私は未成年です!」

教室に戻ると、生徒たちはイーストサイドで「闘争問題」として知られている問題に取り組むため、思考、計算、計算、フラストレーションへの対処など、より哲学的な障害が生じます。実際の闘争 - 問題に取り組む経験 - は、この高校の学習プロセスの典型的な部分であり、社会改革者で廃止論者のフレデリック・ダグラスを引用したポスターがすべての教室に貼られています。進行中です。」

まず、生徒は収集したデータを熟考するという課題に直面します。フィールドワークの間、彼らはそれぞれ観察者、歩行者、記録者の役割を担っていました。オブザーバーは、選択した建物の向かい側のポイント A に立っていました (人気のある選択肢には、ピザ屋とマカロニとチーズのレストランが含まれていました)。 2 つの iPhone アプリを使用して、点 A から建物の最上部までの仰角と、建物の基部にある点 A から点 B まで歩行者が移動した距離を測定しました。これら 2 つの測定値から、直角三角形に関する重要な情報が得られました。そこから、これまでクラスで三角法について学んだことを使用して、建物の高さを計算するタスクが課せられました。しかし最初は、重々しい視線、眉をひそめ、消しゴムの粉が立ち上る中で何度も描き直された図表、そして困惑の集合的なうなりがあります:

「わからないよ、男。本当にわかりません。」

"ヘルプ!助けて!」

しかし、彼らは教師からあまり助けを得られません.

「私は彼らに答えを与えるのをやめた教師です」と30代のミダは言いました. 「私たちが行うすべての単元で、私は彼らに次のように警告します。「必要なツールを提供しますが、何かを行う方法を教えることは決してありません.あなたはそれを行う方法を理解しなければならず、答えを見つけ出さなければならず、なぜその答えがそれであると思うのかを私に証明しなければなりません.失敗できる唯一の方法は、あきらめた場合です。辛抱し続ければ、挑戦し続ければ、これを乗り越え続ければ、これを手に入れることができます。しかし、あきらめたら失敗します。」

Midha は昔から数学が好きで、簡単に好きになりました。 10 年生のとき、代数の教師が黒板で標準的な「チョークとトーク」を行ったおかげで、彼女は自分の能力に疑問を感じました。しかし、ウェスリアン大学の 1 年生のときに、彼女は数学を芸術と見なす教授から微積分を学びました。 「彼が言ったことはすべてとても深遠でした」と彼女は思い出しました。 「私は、「ああ、なんてこった」のようでした。これはこれまでで最もクールなことです。彼女は数学を専攻し、音楽も専攻しました。彼女はクラシックギターを弾きます。

Midha は、中学生向けのサマー セッションで音楽、数学、スペイン語、ウェブ デザインのレッスンを行った後、大学在学中に教師になることを決意しました。彼女はファスト トラックのニューヨーク市ティーチング フェロー プログラムに応募し、大学を卒業してすぐにブルックリンの学校に入学し、同時に教育の修士号を取得しました。彼女は 4 年間教鞭をとり、その後 2 年間の回り道をして国を離れ、インドのファッション ハウスでマーケティングと広報の仕事をしました。彼女が家に帰ったとき、彼女は子供たちが恋しいことに気づきました。 「それからイースト サイドを見つけて、『これだ』と思いました。ここは特別な場所です。」

イースト サイド コミュニティ ハイ スクールは、1970 年代にさかのぼる小さなオルタナティブ シティ ハイ スクール運動の第 2 波の一部として、1992 年に開校しました。これは、パフォーマンスベースの評価を支持して画一的な標準テストに反対する州全体の 28 の学校のグループである、ニューヨーク パフォーマンス スタンダード コンソーシアムの一部です。

「Learning by Heart」というタイトルの学校に関する最近のケーススタディでは、イーストサイドは、学業の厳しさと生徒との個人的な関係を優先することにより、成功を収めている場所であると説明しています。生徒たちは、2012 年に学校の 90 年前のレンガ造りのファサードが鉄骨から外れていることに管理人が気づいたとき、イースト サイドがいかに特別であるかを理解するようになり、緊急避難と、窓のない人間味のない学校への 5 か月の移転が必要になりました。高セキュリティバンカーに似た教室。対照的に、イーストサイドにはたくさんの愛があります。 「教師は私たちの子供たちを愛し、子供たちは私たちを愛しています」と、一部の生徒にとってもう一人の親のようなミダは言いました.この学校は 6 年生から 12 年生までを対象としており、多様な生徒が集まり、そのほとんどがローワー イースト サイドに住んでいます。学生の半数以上がヒスパニック系で、約 4 分の 1 がアフリカ系アメリカ人です。約 4 分の 1 が特殊教育を受けています。しかし、100% は、学習のてことしての探究によって支配されています。

闘争問題の 2 日目に、ミダはスラックスと T シャツを着て、絶え間なく動き続けることができるニューバランスのランナーを身に着け、生徒たちに厳選された情報と指導のみを提供します。

「私はあなたの闘争の問題について1つのヒントを与えるつもりです」と彼女は言います. 「これが私があなたに与える1つのヒントです。目標は、建物の全高を見つけることです.全高。全高。

「覚えておいてください:仰角はどこから測定されましたか?目。ですから、絵を描いたり計算したりするときは、そのことを覚えておいてください。あなたの仕事は、建物の全高を計算することです。 … 覚えておいてください:目の高さを測定したのには理由があります。目の高さを測ったのには理由があります」思春期の脳に浸透するには、繰り返し、さらに繰り返しが重要です。

Midha はまた、目の高さをインチで、建物の距離をマイルで測定し、ワークシートでは建物の高さをフィートで求めていることを生徒に指摘して、ある種のボーナス ヒントを提供します。それで、彼女は生徒たちを自分のデバイスに任せます—「頑張ってください!」

彼女は部屋を一周し、進行状況を調査しながら、単純にこう尋ねました。 ……どうして意味がないの?」彼女のヒントにもかかわらず、目の高さの関連性はとらえどころのないことが証明されており、インチ - フィート - マイルの変換は混乱しています.彼女は、グループと 1 対 1 でアドバイスを繰り返した後、再びグループを解き放ち、次のように宣言します。

「いや、戻ってきて!」ファビアンは欲求不満で鉛筆をひっくり返し、目を痛めながら嘆願します。

Midha と彼女の同僚のイースト サイドの数学教師は最近、生産的な数学ディスカッションを編成するための 5 つの実践を読みました。 、マーガレット・シュワン・スミスとメアリー・ケイ・スタインによる。彼らは、金曜日のミーティングで章ごとに分析し、議論しました。 「それは、厳格さを増し、比率を高めるという考え、そして子供たちとの会話についてです」とミダは言いました. 「比率」とは、生徒が自分で行う発見と学習の量と、教師から受ける明確な実地指導の量を指します。 「基本的に、それは思考比率です」とミダは言いました。 「教師ではなく、子供たちが考えることを行う必要があります。」

子どもたちの思考力を刺激し、知的慣性への傾向と闘うには、細かく調整されたオーケストレーションが必要です。本書の 5 つの実践は、生徒がどのように問題を解決しようとするかを予測すること、彼らの苦労と進歩を監視すること、さまざまな生徒のアプローチを選択してクラスで共有すること、共有されたアイデアを論理的な方法で順序付けること、そしてそれらすべてをカリキュラムの全体的な目標。 Midha が 1 つのグループから次のグループへのラウンドを行ったとき、これらの要因は明らかに作用していました。 「彼らがアハハの瞬間を迎えたとき、それはかなり強力です」と彼女は言いました.

「肩の荷が下りたようなものではなく、頭の中で肩の荷が下りたようなものです」と、数学が嫌いだった 16 歳のサバンナは言いました。 「突然、薬か何かを服用したように、リラックスして闘争がなくなり、真実に気づきます。闘争の背後にある真実に気づきます。」

不合格

5 月 27 日金曜日、ボストン西部の裕福な郊外で、Aaron Mathieu は、Acton-Boxborough Regional High School の高度な配置生物学の学生にラボ実験を紹介します。 42歳のマシューはボーイッシュな容姿と、真面目とのんびりした声が交互に聞こえる。彼の生徒たちはグループに散らばり、騒々しくおしゃべりをします。マシューは、試験管を準備するようにリマインダーで彼らを拘束します。それから彼はリラックスして、生徒たちを天使と呼びます。これは、高校の物理の先生から聞いた愛情のこもった言葉です。 (彼はそれが好きです。なぜなら、「男」とは異なり、「誰もが平等に気分を害するからです」と彼は言いました。)その日遅く、別のクラスで、彼は最近の職業遠足について語呂合わせを思い出し、眼科医が何をするかを学びました。非常に目を見張るものがあります」)。彼の生徒たちは先生をからかって、彼をオタクと呼んでいます。

6 年前、Mathieu は優等生のクラスで危険なプロジェクトに挑戦することにしました。生徒たちは学校の敷地から虫を集め、すりつぶして DNA を抽出しました。次に、昆虫の生殖管内に生息する特定の種類のバクテリアから DNA を分離しようとします。

実験は複雑で、Mathieu と 2 人の同僚の教師は数年かけて熟考し、それを試みるかどうかを決定しようとしました。彼らがこのプロジェクトに惹かれたのは、分子生物学の概念と技術を実際の科学の実践と組み合わせたからです。実験が成功した場合、生徒たちは新たな発見をする可能性がありました。つまり、Wolbachia pipientis として知られる特定の微生物を持つ新種を特定することです。 、そして細菌の新しい株を発見すること。しかし、このプロジェクトは大失敗に終わる可能性があります。 DNA を抽出し、配列をコピーし、それらを分離し、データを視覚化するという斬新な実験的ステップを 5 日間かけて行うとしたら、私たちは教師としてどのように感じるか、また学生はどのように感じるかを心配していました。 、とマシューは言いました。

生物学カリキュラムの既存の実験プロジェクトのほとんどは、初心者向けの料理本のレシピのように設計されており、ほとんどの場合、計画どおりに結果が予測可能でした。しかし、マチューは生徒たちに科学の本質、つまり探求する感覚、発見の高揚感、失敗の挑戦に触れさせたいと考えていました。そのためには、セーフティネットを取り除かなければならないことを彼は知っていました。 「イノベーションを起こすためには、リスクを冒す必要があり、子供たちをリスクを冒す状況に置く必要があります」と彼は言いました。効果のないラボで 1 週間過ごすことは、限られた時間やその他のリソースを浪費し、学生のやる気を失わせるリスクがあります。 「データをうまく生成できなかったとしても、教師も生徒も、プロジェクトを試みることで多くのことを学べることに気付きました」とマチュー氏は言います。 「私にとって唯一の時間の無駄は、学生が経験から学ばないことです。」

ボルバキアでの最初の試み マチューと彼の同僚が恐れていたように、ラボは終了しました。学生たちは取り乱し、プロジェクトが完了したとき、失敗と明確な答えの欠如だけに集中しました。しかし、マチューはその反応を利用して、彼の教育哲学を形作りました。 「私は、彼らが科学のプロセスについて十分に学んでいない兆候だと考えました」と彼は言いました。 「それは、カリキュラム全体に科学のプロセスを組み込む必要があることを意味していました。」

Mathieu は時間をかけて学生と一緒に研究室を分析し、どこが間違っていたのかを突き止めようとしました。彼は、科学者が結果の原因となる変数を分離するのに役立つ実験制御について、学生が深く理解していないことに気付きました。この実験では、コントロールは分子生物学キットからのいくつかの既製の DNA でした。学生たちは、昆虫とキットの両方から DNA を増幅しました。昆虫と対照 DNA の両方で増幅プロセスが失敗したことが判明し、それが問題の原因であることが示唆されました。 Mathieu と彼の生徒たちはプロセスを改善し、今ではうまく機能していますが、まだ完全ではありません。 「今年の 1 つのクラスには驚くべきデータがあり、1 つのクラスにはほとんどデータがありませんでした」とマチューは言いました。

それから 6 年が経った今、科学のプロセスはマチューの教えの重要な部分になっています。学生のいくつかのクラスは成功した結果で昆虫実験室を実行しました。しかし、おそらくもっと重要なことは、結果がうまくいかなかった場合に、結果をよりよく分析できることです。 Mathieu と彼の生徒たちは、コントロールの重要性や実験計画のその他の側面について 1 年を通して話し合い、生徒たちは現在、独自の実験を計画しています。彼らは、マウスがピーナッツ バターとヌテラのどちらを好むかをテストしました。 (マウスはヌテラに対して相反する感情を持っています。)彼らは芝生を燃やして、放火後に草原がよりよく成長するかどうかを調べました。 (もちろん、保護者の監督の下で。)彼らは、植物がアルミニウム、ニッケル、鉛にどのように反応するかを分析しました。 「学生は選択をするために、質問をする必要があります」とマシューは言いました。 「彼らが実際に科学を行っているのであれば、ある程度の選択と制御が必要です。」

「アーロンの目標は、学生が教室で実際の科学を行うことであり、シミュレーションを行ったり、答えがわかっている実験を行ったりすることではありません」と、全米生物学教師協会の優れた生物学教師賞を管理するアクトン ボックスボローの同僚であるブライアン デンプシーは述べています。

マシューが昨年優勝しました。

教職歴 20 年のベテランであるマシューは、10 年前に国家委員会の資格を取得した後、ひらめきを経験しました。教え始めた最初の 10 年間を振り返ってみると、教材の提示方法を考え出すなど、教える技術に多くの時間を費やしていることに気付きました。 「私は自分自身を生物学の教師だとは思っていませんでしたが、むしろ教師だと思っていました」と彼は言いました。 「しかし、私は自分がどれだけ科学を教えているのか疑問に思い始めました。私は科学のプロセスと科学の性質を提示していたのでしょうか、それとも科学の歴史を提示していたのでしょうか?科学とは一冊の本に書かれた事実の集まりだという考えを私は補強していたのだろうか?」その後すぐに、マチュー、デンプシー、そしてもう 1 人の教師が、科学の経験を教室にもっと取り入れる方法についてブレインストーミングを始めました。このプロセスは、昆虫実験室で最高潮に達しました。

特に新入生にとって、科学のプロセスを教える上で不可欠な要素は、学生が挫折に対処する方法を学ぶのを助けることだと、マシューは言いました。彼は、ある優等生が彼女の生物学の成績にどのようにうんざりしていたかを思い出します。 「それは見るのが難しい感情です」と彼は言いました。 「誰もが苦労して挫折に対処することを学ぶ社会的および感情的な場所にいるわけではありません。」

しわがれを乗り越えるために、彼は学生との関係を築きます。クラス全体で、過去の挑戦と敗北について話し合い、テストやラボで苦労することの意味について話し合います。彼はさまざまな方法で生徒に連絡を取り、授業後に生徒と話したり、電子メールでディスカッションに参加したりしています。彼は、特定の学生が特定の概念に苦しんでいることを指摘し、その学生に座ってそれについて話したいかどうか尋ねるかもしれません.彼はまた、科学以外のトピックについて学生と関わります。 「可能な限り、私は生徒たちと顔を合わせて非公式の会話をするようにしています」と彼は言いました。 「グループが早く終わったら、ゲームやその他のイベントについて話し始めるかもしれません。私はその会話に参加します。」

その結果、生徒たちは失敗した実験に対処する方法を学び、科学において失敗は行き止まりではなく、それ自体が結果であることを理解するようになりました。 「2週間後、ゲルを見て何も見えないかもしれませんが、それは問題ありません。それは科学で起こることだからです」とマシューは言いました.実験が時間の無駄だったと考える代わりに、彼らは何がうまくいかなかったのかを理解しようとします。実験のどの部分が失敗しましたか?次回はどのように改善できますか?一部の生徒は、何が起こったのかを理解しようとするあまり、授業が終わって実験をやり直すために戻ってきます。

エンゲージメント

その同じ金曜日の早い時期に、ベイチェスター中学校のすぐ近くにある車で 2 人の男性が撃たれました。どちらも近くのヤコビ医療センターに運ばれ、そこで1人が死亡します。犯罪現場部隊がベイチェスター アベニューを封鎖します。

登校日は通常通り始まります。昼食後、「カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校」のホームルームの生徒たちが科学のためにカマーの教室に到着します。 「こんにちは、サンディエゴ」と彼女は晴れやかに言います。

「こんにちは、カマーさん!」

「私たちはおもちゃの車のラボを継続するつもりです」とカマーは発表します。彼女の単純な機械ユニットのハイライトであるラボでは、ランプを作成し、ランプをさまざまな素材で覆ったときにおもちゃの車がどれだけ速く転がるかをテストします。 「おもちゃの車ラボで研究しているコンセプトは何ですか?」

ミラニは手を挙げます。 「摩擦」

「摩擦とは?」カマーは尋ねます。一部の学生は、部分的な回答を提供します。 「それは力だと言いました。それは表面に関係していて、物事を遅くすることに関係していると言いました。すべてを 1 つのきちんとしたパッケージにまとめられるのは誰ですか?」もう一度試した後、彼女はキャメロンを呼びます。キャメロンは穏やかな話し方で、最初はうまくいかなかったのですが、今では彼女のトップクラスの生徒の 1 人です。

「物体の移動を容易にしたり困難にしたりするのは、2 つの表面間の力です」と Cameron 氏は言います。

すぐに、生徒たちはグループで騒ぎ、役割を定義し、スロープにどのカバーを付けるかを決定します.カマーは彼らの進歩を監視しながら、個々の生徒を調べて理解度を測ります。 「なぜ車の速度が従属変数なのですか?」キャメロンのチームメイトの 2 人は、ランプの覆いに依存していると正しく説明しています。次に、「独立変数は何ですか?」

「ランプのカバーです」と誠実に答えます。彼ともう 1 人の男の子は、TRAIN を表すオレンジ色の文字が入ったベイチェスター ブルーのヘッドバンドをしています。

「あなたの実験のコントロールは何ですか?」カマーは尋ねます。これはグループを困惑させます。 「では、コントロールとは何ですか?」彼女は突きます。空白の凝視。クラス全体でこれらの概念を復習することにしました。

全員が基本を理解したことに彼女が満足したら、子供たちは材料を集めてスロープを作りに行きます。教室は建設ゾーンになります。校長の Shawn Mangar は、Comer のクラスが学校で一番騒がしいと言いましたが、それには正当な理由があります。生徒は「制御された知的カオス」の中で考え、学んでいるからです。

そしてそれはうまくいきます:「私の古い学校ではあまり科学をやっていなかったので、今年の初めは科学にあまり興味がありませんでした」とShomariは授業の後に言いました.しかし今、彼女は言いました。「私が科学で気に入っているのは、さまざまなことを試すことができ、他の人の意見に異議を唱えることができるところです。」

同様に、キャメロンは、彼の古い学校では「教科書などを読むだけです」と言いました。彼は実践的なプロジェクトと、カマーが「より深く物事に取り組む」という事実が大好きです。昨年の冬、地面に氷が張っていたとき、彼は摩擦と、滑ったり転んだりしないように足をどこに置くかを考えました。 「私は彼女の教え方が好きです」と彼は言いました。 「彼女は決して急がない。時間をかけるだけです。」

学校の創設者は、科学がベイチェスターの焦点になることを決して計画していませんでした。 「このように離陸するとは予想していませんでした」と Mangar 氏は言い、Comer 氏の功績を称えました。 「生徒が 2 つか 3 つのクラスで苦労しているのを見ることができますが、突然、彼らは理科のクラスのロックスターになります。」

モデル

マイケル・ジトロは、5 月 12 日木曜日、マンハッタンのミッドタウンのふもとにある 11 階建ての公立中学校と高校で、物理学 1 のクラスを教えています。 . 「こっちに来てもらってもいいですか?ダニー、あなたはもう少し近づきたくなるでしょう。シャワーを浴びた;においがあまりしません。」

生徒たちは先生の周りに集まります。禿頭でひげを生やし、いつものように科学をテーマにしたネクタイを締めているジトロは、2 つのゼンマイ式おもちゃ、車とアヒルをテーブルの上でぐるぐる回します。

「このゼンマイ式おもちゃを巻いたとき、中に何が入っているか知っている人はいますか?」彼は尋ねます。

「春だ!」

「それはバネか、ある種の伸縮性のある輪ゴムの素材かもしれません」とジトロは言い、これらのいずれかが、アヒルが歩くときに運動エネルギーとして解き放たれる位置エネルギーを蓄えることができると説明します.

これは、ジトロが慎重にキュレーションしたエネルギーに関する 1 か月単位のユニットの初日です。生徒たちは、デモンストレーション、思考実験、ビデオ クリップを熟考して、エネルギーがあるタイプから別のタイプに変化する方法に慣れ、一連の棒グラフでそれらの変化をグラフ化する練習をします。

「簡単な免責事項 — エンジニアは実際にこれらの棒グラフを分析に使用していますか?いいえ」とジトロは言います。 「彼らは、エネルギー変換がどのように起こるかを深く理解しているため、頭の中でこれを行います。頭の中でこれらのことを快適に行えるようになるまで、今のところこれらを紙の上で行っています。そして、これらが実際に数学的モデルを作成するための出発点になるでしょう。」

This evening, the students will write a one-page “mastery reflection” on using bar charts to model energy transformation. And through further experimentation in the weeks that follow, they will develop mathematical abstractions or “models” that describe energy’s behavior, essentially deriving for themselves the equations that most physics students memorize from textbooks. Called “modeling instruction,” it’s a pedagogical approach that is surging in popularity among physics teachers. Modeling instruction won the 2014 Excellence in Physics Education Award from the American Physical Society and has been shown to yield higher scores than traditional courses on the force concept inventory, a test that gauges students’ conceptual understanding.

But Zitolo did not always teach this way. When he first entered the profession — and his seventh-floor classroom at School of the Future — almost 10 years ago, he felt as though he was drowning in a sea of concepts. He was somehow supposed to instill a thorough knowledge of forces, kinematics, energy, electricity, magnetism, waves, modern physics and more in students whose prior notion of physics consisted of the word “gravity.” He couldn’t keep up. And the students who passed through his class rarely went on to study science or engineering in college.

Meticulous about everything from beard trimming to his annual go-for-broke Halloween costumes (which earn him schoolwide respect), Zitolo was obsessed with self-improvement. “I was of this mind that there is a perfect way to teach physics, and I just have to figure out what that perfect way is,” he said. “I was very hard on myself my first couple of years. I literally, one year to the next, could not look back to what I did in previous years, I thought it was so horrible.”

The biggest breakthrough came the summer before Zitolo’s fifth year of teaching, when he attended a three-week workshop on modeling instruction. Mark Schober, a physics teacher and former president of the American Modeling Teachers Association, called modeling “a grassroots movement” that grew in the 1980s largely out of the classroom practices of an Arizona physics teacher named Malcolm Wells. The movement has expanded to 78 workshops this past summer; as of 2015, more than 10 percent of the nation’s physics teachers had attended one. In modeling courses, instead of first teaching physics concepts in the abstract and then connecting them to the real world through labs, teachers have students experiment with model systems — a windup toy, for instance, or a cart held by a pulley at the top of a ramp — and guide them as they develop mathematical models of the systems, which they can then apply to other problems and settings. Modeling instruction is “a lot of Jedi mind tricks,” Schober said. “How do we shape students’ thinking without them knowing we are? We want them to feel the idea is really theirs — they came up with it.”

Modeling is not a one-size-fits-all teaching method, but is rather tailored by teachers to suit their individual styles and skills. Zitolo, who has an engineering bent, casts his modeling unit on energy as a project to design a roller coaster. In class on May 12, he asks students to imagine dropping a ball from the top of the school building. When the ball hits the ground, he explains, the friction converts some of the ball’s kinetic energy into thermal energy — a form they were supposed to have read about the night before. “Why does this matter?” Zitolo says. “Roller coasters. Even though the tracks are designed to be super smooth, and even though they are supposed to be streamlined to reduce drag, there is going to be drag; there is going to be friction. You guys are going to have to account for that when you design your roller coasters.”

Like East Side Community High School, School of the Future has opted out of the statewide Regents examinations, and this has facilitated Zitolo’s switch to modeling. Student-run experiments and data analyses take longer than lecturing, and so modeling courses typically cover less ground than a traditional physics curriculum. But Zitolo has found that, compared to skimming a sea of concepts, deeper dives instill a deeper appreciation for physics — even in students who are destined for other vocations.

“I’m going for public communications, not anything to do with physics,” said Nikki, who graduated in June and now attends Syracuse University. “But being in Z’s class — it really has opened my mind to, like, wow, this is cool, I get to build things, I get to see how things affect one another.”

Zitolo, now 32, made up his mind to become a physics teacher as a senior at New York University, even though his family, friends and mentors encouraged him to “do something real” with his physics degree first. Teaching “gives me the ability to be creative,” he said. He gets to share his passion for physics with students “and hopefully inspire that same passion in them.”

TRAIN

A week into his May unit on roller coasters, Zitolo and about a dozen other science teachers meet at a building on 21st and Broadway for pizza and an evening course led by Channa Comer. Comer and Zitolo have been friends for years, having participated in many of the same professional development (or “PD”) activities. After chatting with him and other participants about the rapid approach of summer, Comer launches into the benefits of using primary sources such as maps, original documents and diagrams in the science classroom to help engage students.

During the course, which is sponsored by Math for America, a nonprofit organization that aims to improve public math and science education by providing a comprehensive support system for teachers, the cohort brainstorms ways of integrating primary sources into their curricula. “Sometimes when I start a unit, I have them do research on, like, the physics of roller coasters,” Zitolo says to his tablemate, Bianca. “But maybe I could also kick them off with, like, a little bit of the history of roller coasters that I could provide, to see how they’ve evolved over time.” He begins to search the Library of Congress website.

When Comer decides to do something, she’s not one to just dip a toe. Years ago, at a bodybuilding show, she looked at the woman who won and thought, “I could do that.” So she did, training two to three hours a day, radically altering her diet, taking supplements like medium-chain triglycerides (to burn fat) and zinc (to increase blood flow and vascularity), tanning and practicing poses. “It’s a crazy lifestyle,” she said. “It costs so much and you can’t walk past a store without checking your muscles.”

She quit bodybuilding after four years out of concern for her metabolism, pocketbook and humility. Now she’s into yoga and belly dancing, both of which she’s certified to teach. When she became a science teacher nine years ago, she threw herself into the work just as she does with everything else. She trained hard over weekends and summers, partly for the extra income — some fellowships offer generous stipends — but also to “build my own content knowledge, because I came into this with a scattering of science in different areas,” she said.

“She’s done more PD than any other teacher I know and is constantly integrating what she learns into her curriculum,” Zitolo said in an email.

Among her teacher friends, Comer said, “I’m known as a PD junkie.” During her first year as a teacher, she wanted to observe more accomplished teachers, but she and the other two science teachers at Urban Assembly Academy were all relatively inexperienced. So she convinced her principal to let her spend one day a month observing teachers at other schools. One month, she visited New Design High School on the Lower East Side to observe David Rothauser, a teacher known for giving students ambitious design challenges. “That’s when I started doing engineering design challenges and using ‘design thinking,’” she said. Design thinking involves figuring out “all the different ways we could solve a problem.” Many of her former high school students who didn’t go to college now work for the parks department, in restaurants or in retail. Without marketable skills like design thinking, she said, “those are the only things that are available to them. I think the whole system needs to be changed and the focus needs to be on thinking and not so much on facts.”

Rothauser said he was immediately impressed with Comer’s ability “to improvise within the system,” adding that “it felt wonderful to be discovered by her in that way.” Comer went on to become a master fellow in the Sci-Ed Innovators program he was helping to run, and later joined the leadership team.

Over the next several summers, Comer participated in teacher research programs in neuroscience, nanotechnology and robotics, took workshops in molecular biology at Cornell University, and participated in sea scallop surveys with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Comer and Zitolo became fast friends during the Summer Research Program at Columbia, which she considers one of the best PD opportunities because it runs for two consecutive summers in the same laboratory, offers a generous stipend, involves collaboration with experts, and focuses on both research and pedagogy. The two have also participated together in the Smarter program at New York University’s Polytechnic School of Engineering, and they were Sci-Ed fellows the same year. All three of these extended programs provide training that goes well beyond what’s offered in the one-off workshops that many teachers attend. They also include “a mechanism for follow-up to assess implementation and effectiveness of the PD,” Comer said. “In my experience, the programs that I have participated in that fit these criteria have had the greatest impact on my teaching practice.” However, a paradigm shift in professional development will not come easily. “Teachers have been conditioned to expect PD where they walk away with something that they can use in their classroom immediately, rather than working through a process that may take some time to develop and yield results.”

In Acton, Massachusetts, Aaron Mathieu networks with scientists and other teachers, figuring out how to improve experiments, convincing researchers to donate agar plates or other materials for new projects, and arranging lab visits for students. Everyone Mathieu meets is fair game. He has recruited biologists he met at his sons’ elementary school picnics and soccer games to host career shadowing visits.

Mathieu works with Natalie Kuldell, an instructor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who runs the BioBuilder Educational Foundation, a nonprofit organization that teaches synthetic biology and runs summer workshops to train teachers in bioengineering. He’s also been in touch with Seth Bordenstein, an evolutionary biologist at Vanderbilt University who helped develop the insect DNA lab that Mathieu implemented five years ago.

Soni Midha’s approach to professional development is immersive, in part out of necessity. She teaches four classes and meets with a math coach and her fellow math teachers. “We geek out,” Midha said. They talk lesson plans and curriculum goals, and they often begin a meeting by doing a math problem themselves.

Broadly speaking, their goal is to reflect upon teaching and to improve. With that in mind, Midha and her colleagues read the book A Mathematician’s Lament , a landmark critique of the nightmarish state of mathematics education by Paul Lockhart, a math teacher at Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn. Lockhart chronicles the standard rote approach, in which students are told, “‘The area of a triangle is equal to one-half its base times its height.’ Students are asked to memorize this formula and then ‘apply’ it over and over in the ‘exercises.’ Gone is the thrill, the joy, even the pain and frustration of the creative act.” Lockhart argues that mathematics should be taught as “an art for art’s sake”:

Mathematics is the purest of arts, as well as the most misunderstood.

… If there is anything like a unifying aesthetic principle in mathematics, it is this:simple is beautiful . Mathematicians enjoy thinking about the simplest possible things, and the simplest possible things are imaginary .

… That’s what math is — wondering, playing, amusing yourself with your imagination. …

… People enjoy fantasy , and that is just what mathematics can provide — a relief from daily life, an anodyne to the practical workaday world.

For Midha, the daily regime has her watching the clock, timing lessons down to the second. She arrives at school as early as 7:30 a.m. The final bell rings at 3:30 p.m. She has a 50-minute lunch period, which she often spends meeting with students or keeping up with work. She tries not to take her grading home, but she often does.

Sometimes she gives over her spare time to professional development. A few years ago she took a Math for America workshop led by the Stony Brook mathematical artist and educator George Hart. He entranced a classroom of teachers with what he calls a sculptural “barn raising” — the collaborative construction of a giant starlike polyhedral sculpture suspended from the ceiling. The sculpture consisted of 60 identical interlocking cardboard pieces, which formed the 20 faces of a regular icosahedron, with fivefold, threefold and twofold axes of symmetry. “That just kind of blew my mind,” Midha said. Last fall she took a three-part workshop with Hart and then jumped at the chance to have him visit East Side Community High School, where he gave two workshops for students featuring colorful constructions of a “paper triangle ball” and a “paper square ball.” Both were exercises in pattern recognition and visualization, with logical constraints. But the takeaway, Midha said, was, simple:“Math is fun — it can be beautiful; it can be art.”

Working with teachers like Midha, who are rigorously curious and creative, is a joy, Hart said. “There is a wide range of teacher abilities,” he said. “Lower grades often have teachers who are afraid of math, and they pass that on to their students.” Midha, he recalled, was clearly one of those teachers who love being challenged to think in new ways. “And because she enjoys that experience,” he said, “I’m quite certain that she’s going to pass that on to her students.”

The Sci-Ed Innovators program that Comer and Zitolo both attended initiated the second major curricular shift of Zitolo’s career. It was his seventh year in the classroom, and although his switch to modeling instruction was starting to pay dividends, he was still striving for better ways to engage his students. As he developed his curriculum during evening Sci-Ed meetings, he started teaching his Physics 2 class the basics of computer programming, a skill he himself had picked up in college. A few of his best students agreed to showcase their final projects — electronic devices they built and programmed — at Sci-Ed’s 2014 science fair. One of the students, Hannah Parker, designed a health monitor; another built a theremin. On the morning of the fair, Zitolo got up early and baked cookies to calm his and his students’ nerves, worrying that their gadgets might seem trivial or out of place. But as soon as the fair started, their table was swarmed.

Zitolo has since added even more electrical engineering and computer science to Physics 2. This past spring, students built complex devices like motion detectors and musical keyboards. “We’re coding, like hackers! It’s insane,” said Nikki, who built a fan that turns on in high humidity. Each year, several students in the class participate in a citywide program called ACE (Architecture, Construction, Engineering), and many have earned engineering scholarships. Parker, now a math major at the University of Rochester, plans to become a high school teacher. “I want to be Mr. Z,” she said.

Zitolo is now in his 10th year of teaching. Perfection has turned out to be an unreachable goal, of course, rather like the finish line in Zeno’s paradox. But through a series of major and incremental refinements to his pedagogy, he is now a model physics teacher.

ACHIEVE

On Wednesday, June 22, as the school year winds down to its chaotic end, Soni Midha barely has time to think straight. She’s been preparing for her day of “roundtables,” a key component of East Side’s performance-based assessment structure (the school does not participate in the standardized statewide Regents’ examinations, though students do take finals). Each student presents on one of the main subjects they tackled over the year, such as a struggle problem. The students then answer questions from an audience of two peers and a judge, who bestows not grades but a designation of novice, apprentice, practitioner or expert. With eight sessions scheduled over the course of the day, the hallway outside the roundtable room is a constant catwalk of congratulatory razzing.

“How’d you do? Did you fail?”

“No, I got expert!”

“Oh, so you failed.”

Inside, it’s serious business for the presenters, who deploy overhead projectors, cue cards and a personal cover letter, addressed, “Dear Evaluator.” “Welcome to 2016 geometry roundtables,” begins Reon, who notes that he’s into fashion and styling. Wearing a tie-dyed T-shirt with a collage of nuns, skeletons, centipedes, candles, President Obama and equilateral triangles, he presents his building-height struggle problem and his trigonometry work. “I remember the day Soni introduced the topic to us and I said, ‘Trigo what?’” But, as he continues in his letter, “my favorite topic of this semester turns out to be trigonometry, shockingly.”

Janet, in her letter, confesses, “Math and I haven’t always been on good terms. In middle school I used to despise math, I would get so annoyed and frustrated.” But she aces the roundtable, receiving a hug and high-five from Midha and the designation of a grade-10 geometry expert. “Even though I hate something, I’m still going to try,” she says.

In a sense, math is a metaphor for life. And the ability to solve problems and think independently is ultimately the lesson that Midha hopes to impart. “You struggle in math. You struggle in life,” said Midha, who by way of example often tells her students about her struggles with classical guitar. “It takes me forever sometimes to get through a piece. Because it’s so hard, and it sucks, and I don’t want to do it. But I keep going because I know I want a successful outcome, I know I want something really great at the end.”

The same applies to Midha’s goals as a teacher, a job she anticipates doing forever (this year she’s teaching calculus for the first time). “I’m not saying there aren’t days when I’m, like, ‘Uhhhh, I don’t want to do this.’ There are always days where we all kind of just need to take a break. But I’m an educator for life. No admin dreams here. Teacher for life, that’s the goal.”

THANK

On July 28, exactly a month into summer break, Channa Comer is in her Bronx apartment, hemmed in by plants, keepsakes from overseas research trips, a rack of immaculate vintage clothing she plans to sell online, and her two timid cats, Lucy Luu and Teena Turner. She’s sorting through boxes of quirky drawings and letters from some of the estimated 1,000 kids she’s taught over the past nine years. She has moving companies to interview and boxes to pack.

Comer waited until the last week of school to break the news to her students, not wanting it to be a distraction. She was leaving Baychester Middle School. She was done teaching.

“I love these kids. I love them,” she said. “But the system, I think, is extremely flawed, and I just need a break.”

In late August, she began her move to Maryland, where she could commute to the Department of Energy’s Office of Science in Washington, D.C. Months earlier, she had been accepted into the Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator fellowship program, where she hopes to gain a broader perspective on national educational policy.

Why do master math and science teachers, who are passionate about their content area and about developing their craft, who are creative, smart and engaging, and who adore their students — why do they quit teaching? Some have given all they can; they’re burned out from thinking and worrying about their students seven days a week, and from battling with school officials over resources, scheduling, a shortage of support, and an abundance of rigidity. Often these talented, driven individuals are lured away by career options that offer greater professional stature and higher pay. And some are just so naturally adventurous that they were always bound to move on. For Comer, it was all of the above.

“I’m really proud of the body of work that I’ve built as a teacher,” she said. “I don’t know how it will be to be in an office all day instead of in the classroom dealing with students and meltdowns and singing and dancing.” But there are some things about teaching she will not miss:“There needs to be much more flexibility, much more autonomy given to teachers to be able to create and teach to their passion so that they can engage students more deeply.”

By all accounts, including Comer’s, she was given extraordinary freedom and flexibility by her principal and school. “Channa’s earned the ability to do things her way,” said Principal Mangar. “Anytime she’s asked for something, or asked, ‘Can I try something?’ she’s outperformed expectations. I see myself as an offensive lineman — clear the way for her to be able to do good work.”

Still, she got dinged (by administrators other than Mangar) for transgressions like failing to write a learning objective on the board before every class. Comer says she did not have time for that after class periods were shortened from almost an hour to 45 minutes. And besides, her projects and learning objectives, which students recorded in their notebooks, took days or weeks to complete.

“It’s an incredible loss for her students and her school because through all her experiences and bringing them back to the classroom, whatever teacher comes next can’t bring what she brings,” said Michael Zitolo, who admits that the Einstein fellowship is a logical next step for his friend. He hopes her voice will be powerful at the national level, that she can push for fewer discrete standards and more “big-picture ones” like the Next Generation Science Standards.

“You can’t replace someone’s passion,” Mangar agreed. For his part, he hopes Comer will return after her 11-month fellowship ends. “I have a calendar reminder for when to contact her,” he said. “She’s always welcome. This will always be home.”

Even in the chaos of relocating across state lines and dealing with broken elevators, gridlock, a thunderstorm, moving company miscalculations, and other delays, Comer found time to pen a lengthy email criticizing the way science is currently taught:“I think we are approaching it wrong. I don’t think science at the lower levels should be separated into discrete subjects, but rather integrated and taught in the context of real life.”

She said she would be happy to discuss these ideas further, and that she’d be back in New York until August 24, after which she’d be in Maryland “for good.”

Editor’s note:Math for America receives funding from the Simons Foundation.

An excerpt of this article was reprinted on Wired.com.